It is not surprising that people with physical and mental disabilities have much trouble moving around urban cities/destinations. Some areas in the cities are even utterly inaccessible to some of them, as there is a lack of accessible options. When you spend time in cities, it has become increasingly clear that the city plan has prioritized people with no disabilities. Also, depending on the place, culture and society, people with disabilities are unintentionally being treated unfairly.

Also, some countries do not treat people with disabilities well at all, where people with disabilities, if revealed to authorities, are harmed and not regarded since the authorities often view it as an individual problem, thus have no systemic help from transportation systems, policies or their authorities. Another example is where families often hide disabled people since they think their very existence can threaten their status (even though this is the 21st century).

This is, frankly, unsurprising, yet frustrating, as people with disabilities are seen as less of a person, which is not valid. They can eat, cry, sing Christmas songs, work, and they pay taxes like others. Yet, they seem to be disregarded when establishing policies, initiatives, plans, and data collection.

It can even affect the tourism industry as some tourists, travelers, and visitors cannot travel to tourist destinations at all because of the lack of accessible options. This is worse because, according to the World Health Organization of the United Nations, one out of six people have a significant disability. However, there are some government organizations, like in Madrid or Barcelona, that are taking action, which other places and their organizations can get inspiration from.

There are ways to make urban areas and cities more accessible to people with disabilities from an urban planner’s perspective. According to Tari Kaumātua, the Office for Seniors (which is part of the New Zealand government), there is some advice in terms of design and increasing mobility for people with disabilities as well as older people.

- Collaborate with disabled people and elders to create an accessibility plan before spatial planning.

- Reflect community demographics and include multilingual signage in designs.

- Apply universal design standards for accessible streetscapes and buildings with features like color-coded doorways, orienting corners, and highlighted entrances.

- Provide housing options for diverse cultural and personal needs, including multigenerational living and care arrangements.

- Plan accessible public toilets with appropriate spacing in the network basis.

- Design transport waiting areas with seating, weather protection, wheelchair access, and clear vehicle visibility.

- Allocate street width for diverse modes of movement, including mobility scooters and active transport, with well-placed mobility car parks.

- Install safe e-vehicle charging points, addressing trip hazards and quietness as a safety risk.

- Create connected movement networks linking key destinations like parks, libraries, and health services.

Some of these urban features that have been implemented were very subtle. I can understand why these urban features were able to help people with disabilities. These are features and details that future urban planners, including myself, should consider when planning in a city. Moreover, if these suggestions and design tips can be applied to other destinations (especially destinations with little to no accessibility for disabled people), there would be an increase in tourism, which can lead to a rise in economy and the likely delight of the residents.

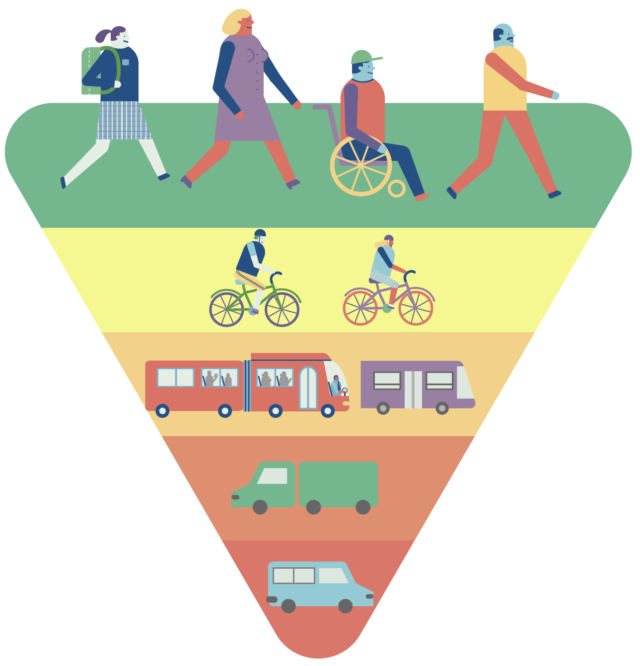

According to the research article ‘Access and persons with disabilities in urban areas’, there is some helpful information, including a pyramid of transport priority.

Three key concepts can be helpful in any city or country and can be applied in real life.

- A two-pronged approach is needed to help people with disabilities have more accessibility in urban areas: systemic change and individual accommodation. Systemic change, including mainstream strategies such as universal design standards and regulations in policy, aligns with targeted individual accommodation that secures accessibility through initiatives for people with disabilities.

- Disability should not be treated as merely a personal trait but as a social interaction with difficulty seeing, hearing, walking, climbing, remembering, concentrating, completing self-care, communicating, or being understood, pressured by an unaccommodating environment.

- Universal Design needs to be applied so designs or plans can be accessible to people from all life paths.

When applied and tailored to each destination, these key concepts can increase the accessibility, safety and overall quality of life for disabled people, including tourists who have disabilities. This is simply simple, yet something that needs to be told. The two-pronged approach to helping people with disabilities makes sense, as while urban design ideas and different plans, policies, incentives and government organizations can help people with disabilities have more accessibility, realistically, not everyone with disabilities cannot be given equal help in any law, policy, incentive or city plan. People with disabilities have different types of disabilities. A person with visual impairment experiences urban city life differently from a person in a wheelchair. Also, some disabilities can be temporary or permanent.

An example of this would be a person who broke a hand who would have a temporary disability, as their hand can heal. At the same time, a person who lost a hand would have a permanent disability. Targeted individual help is helpful as it helps people with disabilities who didn’t get enough help from systemic changes.

Disability is not a trait. People with disabilities do not mean they are less than a person. Traits such as black hair and freckles don’t heavily impact people’s way of approaching life; disabilities do. So, ensuring people with disabilities have rights and including universal/inclusive design is a positive thing.

The information is valuable and can be separated into different categories: laws, leadership, institutional capacity, attitudes, and participation.

Laws

Urban Planners and government organizations can Integrate universal accessibility in policies, legislation, regulations, and standards (including for housing, transportation, and other developments) to establish disability rights as a necessity. This can be great for people with disabilities as they can access services that might not be previously available. This can work mainly because of power. Any business to operate in cities must follow regulations and city laws. Moreover, even though money would need to be sent ( even with government incentives and funds), it can be a net benefit for businesses and government organizations—the residents, especially people with disabilities (including tourists and travelers).

Another way to help people with disabilities have more accessibility would be for Urban planners to implement policies to increase inclusive public transport to reduce the financial burden of mobility for people with disabilities. One example of this is Brisbane, Australia.

Moreover, the publication mentioned that to help people with disabilities; urban planners should create technical standards and regulations for accessibility in urban and transport planning. This can also benefit travellers and tourists who travel overseas to destinations such as Montenegro. Tourists can use buses to travel to nightclubs in places such as Budva without much difficulty.

Leadership

As urban planners ( or anyone with knowledge and experiences relating to people with disabilities), they can give information about inclusive accessibility to policymakers and people in government so they can help and make a difference, such as subsidies and programs. By doing this, the people in power can make an impact when they know what people with disabilities struggle through every day in urban areas. Furthermore, information about inclusive accessibility can be applied to businesses as well, and they can also be given information about the struggles of people with disabilities.

If not possible at the moment, urban planners or any residents, when working together, can elect and appoint persons with disabilities through voting systems. Although not as practical as educating about inclusive accessibility, having an elected person in a position with knowledge can be an option.

Institutional Capacity

If needed, communities, urban planners and organizations can help people with disabilities by creating dedicated institutions to promote universal accessibility, collect and manage quality data, monitor implementation, and evaluate outcomes effectively.

Attitudes

To help change some of the opposing views on people with disabilities, they recommended some of these actions. They all require education, meaning even adolescents might understand it (when applied effectively).

- Help transport staff regularly to improve their ability to assist and interact with people with disabilities.

- Educate the public through campaigns about the rights and fair treatment of people with disabilities and limited mobility.

- Use data to show the challenges faced by people with disabilities and the benefits of accessible public transit.

Also, because people with disabilities experience life differently, they would face risks or uncertainties that might be scarier than to people without disabilities. It might be best for emergency personnel such as ambulances to receive education. Even travelers and tourists with disabilities can comfortably travel to destinations such as Paris, Kotor and Dubrovnik, if they know these types of advice are being applied.

Participation

The information given about helping people with disabilities as normal people can help urban planners (who didn’t initially know how to engage with residents) encourage residents to be part of the solution.

Urban planners can integrate public participation, a key part of urban planning, ensuring the process is inclusive and engages a diverse group of local residents at every stage. Depending on the city to city, country to country, this can mean online surveys for the public to participate in, public meetings in community centers where everyone can voice their opinion, or local residents and people with disabilities bringing up their problems to the public and government organizations.

Have local councils and communities organize public meetings and workshops that are easy for everyone to join, with accessible formats, convenient times, and flexible ways to share feedback. Depending on whether or not the cities have the technology (and public wi fi) to do so, online Zoom meetings can be more convenient for everyone. The best places for public workshops would be in local public buildings such as the community center or public squares.

Use tools like accessibility audits and focus groups to evaluate public spaces and transportation, identifying and removing user barriers. Furthermore, to make sure the accessibility audits work well, public users should be encouraged to share their experiences with others in public spaces and transportation systems.

Government organizations, planning consultancies, and organizations should adopt accessible and open-source technologies to improve data collection and provide better access for people with disabilities, promoting more inclusive city planning. Moreover, since people with disabilities experience urban city life differently from other people, they should have their categories and sub-categories. People with disabilities have different impairments, like deafness and blindness.

This article shows how people with disabilities can be helped to have more accessibility in urban areas. People with disabilities participate in urban areas, so they should have full access to public places without feeling uncomfortable. Tourists with disabilities should be able to go to beaches without much difficulty. Travellers with disabilities should not feel unsafe when strolling through the night markets in Budva. When people with disabilities want to travel overseas, they should have a wide array of tourist destinations to choose from and have fun without any difficulties (as the destinations improve their accessibility policies and practices). Hopefully, one day, all people with disabilities can travel to any tourist destination without feeling any different to people without disabilities.

Author:

Xiuwei Zhang

Urban Planner for Tourist Destination intern

University of Auckland, Auckland, NZ

Mentor:

Marija Lazarevic, MSc

CEO at MariXperience ltd.